Phase-Field Tutorial: Spinodal Decomposition of Iron-Chromium Alloy

Introduction

The purpose of this tutorial is to help new users learn the process of developing a phase-field model in the MOOSE framework. It gives step-by-step instructions for development and introduces various built-in tools that help the system run better. This tutorial does not explain the basis of the phase-field theory or cover object development in MOOSE.

Problem Setup

We are interested in using phase field to model the spinodal decomposition of an iron-chromium alloy at 500°C over a time scale of one week. We will perform the simulation on a two-dimensional 25nm × 25nm surface. The interactions between iron and chromium are relatively simple and depend solely on the concentrations of the two species. Therefore, the system can be modeled using the Cahn-Hilliard equation with no external energy sources:

In this case, is the mole fraction of chromium (unitless), is the mobility of chromium (), is the free energy density (), and is the gradient energy coefficient (). Values for these terms can be looked up in a database or calculated in a thermodynamic software package. In this problem, values were fit to equations which rely on the equation

The free energy is fit to

While the mobility is fit to

The coefficients used in these two equations at 500°C are

| f Variable | f Value | Cr Variable | Cr Value | Fe Variable | Fe Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -24468.31 | -32.770969 | -31.687117 | |||

| -28275.33 | -25.8186669 | -26.0291774 | |||

| 4167.994 | -3.29612744 | 0.2286581 | |||

| 7052.907 | 17.669757 | 24.3633544 | |||

| 12089.93 | 37.6197853 | 44.3334237 | |||

| 2568.625 | 20.6941796 | 8.72990497 | |||

| -2345.293 | 10.8095813 | 20.956768 |

while the coefficient is .

The alloy is 45 wt% chromium and is initially uniformly distributed, with minor random variations.

Problem Analysis

Units

The initial condition is given in weight percent, but the equations are given to us on a molar basis. Therefore, we can use the molecular weights of chromium to convert the initial condition from 45 wt% to 46.774 mol% chromium.

In units of meters, the mesh would be entered into MOOSE as by . However, MOOSE has a built in tolerance that will not allow mesh nodes to be any closer together than . To get around this we need to change the length scale to units of nanometers. To prevent the values from becoming too large or too small, we will also change the energy scale to units of electron volts. The conversion from meters to nanometers is . The conversion from joules to electron volts is . Rather than converting all of the values in the table above, we will program these conversions into the input file and do the conversions within the file.

Plots

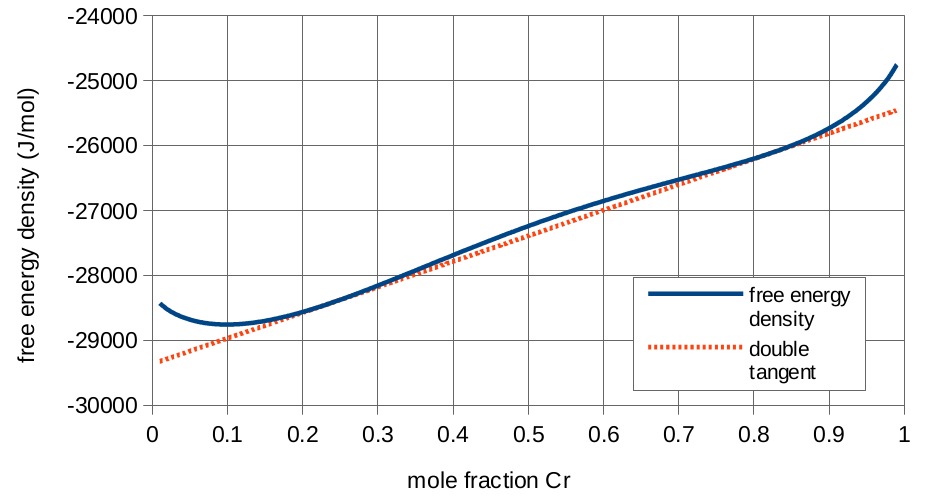

Free energy density curve for iron-chromium alloy.

The free energy density equation given above is a double-well energy curve, meaning the alloy will want to decompose into two phases with distinct concentrations. The equilibrium concentrations are found at the double tangent line of the free energy density curve. The double tangent line can be solved using a numerical solver. The equilibrium concentrations are 23.6 mol% and 82.3 mol% chromium. We will refer to these as the iron and chromium phases respectively. The curve and the double tangent line are shown to the right:

If we perform a material balance on the surface using the initial condition, we find that 39.5% of the surface should decompose to the chromium phase, with the rest decomposing to the iron phase.

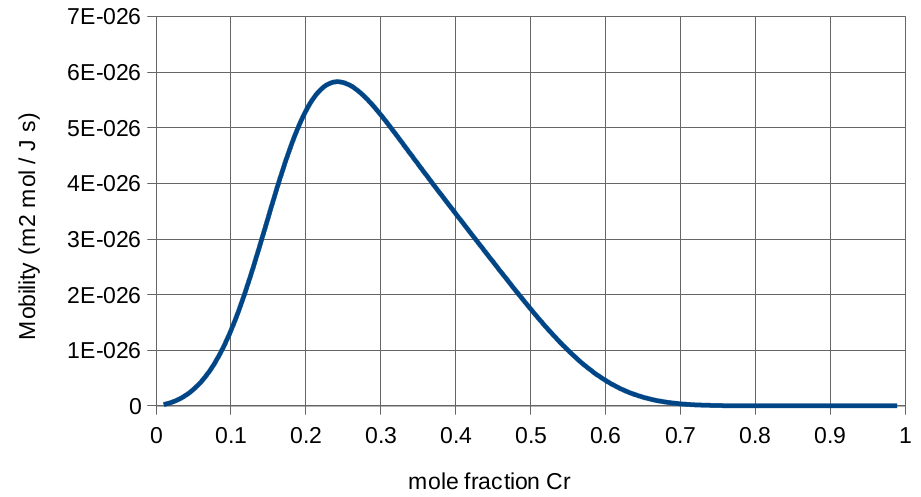

While the curve to the right shows that the mobility varies greatly depending on the concentration, we will begin by assuming that is constant. There are a lot of values we could choose, but a reasonable one would be the value at our initial condition. At 46.774 mol% chromium, the mobility is .

Mobility curve for iron-chromium alloy.

Expectations

We expect three things from this simulation. First, the surface should decompose into the iron and chromium phases at the equilibrium concentrations. Second, the decomposed surface will minimize energy by minimizing the interface contact between the two phases. It does this by shaping the regions as circles or large stripes. Third, most phase field problems reduce the free energy of the surface in an S-curve shape. That is, at the beginning and end of the simulation, there is relatively little change in the free energy of the surface, but there is a rapid decrease somewhere in the middle. We will look for each of these as we develop our model.

Simulation Development

We will develop a full working code in 5 steps. Each step will build on the code that was written in the previous steps.

Step 1: Make a Simple Test Model

We will begin by developing the simplest model we can and checking one of our expectations about the result.

Step 2: Make a Faster Test Model

Now that the simplest model is working, lets add some features to improve how it runs.

Step 3: Add Phase Decomposition to the Model

Now that the model is working and running fast, lets put in the real initial conditions and the real time frame and see if the surface decomposes like we expect it to.

Step 4: Make the Mobility a Function

It is time to use the mobility function instead of a constant.

Step 5: Check the Surface Energy Curve

Let's optimize our convergence and see how the free energy of the surface changes with time.

Conclusions

We are now done with this tutorial. We started by defining the problem and the equations and variables that would lead to a solution. Then we developed some expectations for how the problem would behave.

Then we started developing our simulation. We started with the most basic model we could get, then added features to make the model converge faster. As we developed the model we made it more realistic and kept adding features to tell us more information about the system and to help it converge faster.

Along the way we talked about the various blocks and parameters that are required for MOOSE to work properly as well as some of the blocks and parameters that can help it run smoothly. Of course there is a lot more that MOOSE can do. Keep exploring the Wiki to find more features.